Not too long ago I stumbled across an old book full of wisdom and answers to my biggest economic questions: Why does a growing economy come with increasing levels of poverty? Why can nobody fully own a home? Why do downtowns look like crap? Why are the paychecks shrinking but the country is more productive than ever? Why is the rent so damn high?

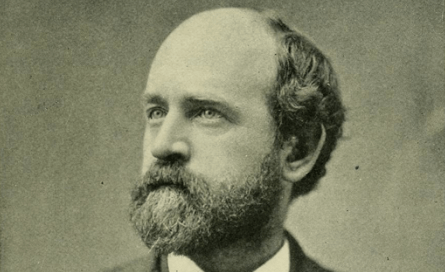

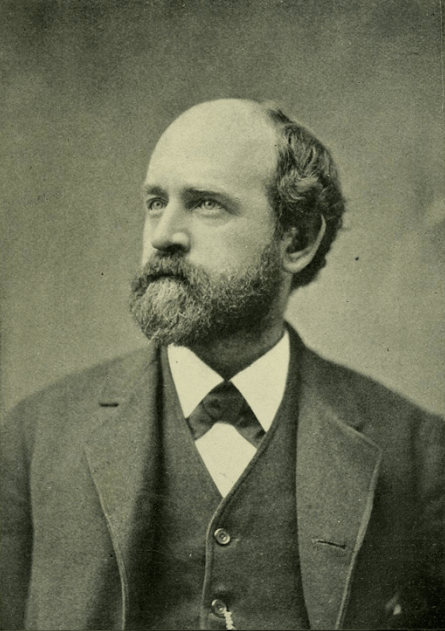

I blew off the dust and mold to see the title, “Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth: The Remedy.” written by a plain-looking and plain-named fellow: Henry George, the original homeless economist.

Back then, I was a low-level employee at Gray Economics, Inc., a corporation whose motto was “All gray, every day.” I would spend all day crunching numbers at a tiny desk, and work on the most useless economic projects, like bagel industry data analysis and the theoretical gas prices of the world in the American animated racing comedy film franchise produced by Pixar Animation Studios for Walt Disney Pictures, Cars.

That day, I grew tired of the work and decided to take a trip down into the deepest depths of our archives; the dumpster, where they threw all the old economic ideas away, and where I discovered the book that changed the trajectory of my entire career.

The author was a political economist, journalist and New York City mayoral candidate with more clout than Karl Marx had when he was alive at the time, yet he achieved all of this with no formal education.

Who was Henry George?

Henry George worked as a day laborer and later as a typesetter in a newspaper printing press in California during the years leading up to the American Civil War. He witnessed the most desperate poverty on his travels across America and on his sea voyages to places like British-colonized India, but noticed all of it was happening at the same time as a revolution of new industrial technology and inventions that were transforming life for millions.

But George during the first several years of life with his young family found himself in desperate poverty. This was during a time in the 1800s when economic crashes were frequent and the government could barely put up a telegraph, let alone provide unemployment insurance or food stamps.

“He left the office. But he could not go home empty-handed. Somehow he must get food for her (George’s second baby). She was starving, the doctor had said. The girl was hungry. And he had brought her to this from a home of comfort and plenty.

He paced the streets in panic. The day was gray and damp; there had been a light rain. Everyone he passed looked cold and poor. He was growing desperate. At last a well-dressed man appeared.

The shivering youth walked straight to the stranger and abruptly stated that he wanted five dollars. ‘What for?’ demanded the man, studying the gaunt face. ‘My wife has just been confined and I have nothing to give her to eat!’

Whether it was compassion for suffering or fear of attack, the man gave the money without further question. ‘If he had not’ said Henry George, long later, ‘I think I was desperate enough to have killed him.’”

“Henry George: The Formative Years” by Anna George de Mille

George’s journalism career and popular writings helped him finally earn enough of an income to rescue his family from starvation.

Finding the problem

But his biggest idea came one day in 1871, after making small talk with a local asking about the price of a nearby piece of undeveloped land, the realization (some would say revelation) hit him:

“I asked a passing teamster, for want of something better to say, what land was worth there,” George later wrote. “He pointed to some cows grazing so far off that they looked like mice, and said, ‘I don’t know exactly, but there is a man over there who will sell some land for a thousand dollars an acre.’ Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth. With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege.”

He became inspired to figure out what was going on with the complex and mysterious economic system that affected the lives of so many common people, and he decided to do something about it.

He had studied up on the works of the original economic writers like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, J.S. Mill and the French Physiocrat school, and became a self-taught political economist (in the old days political theorists and economists were both called “political economists” as the economic system was rightfully not viewed as separate from the political system).

Progress and Poverty

George clawed him and his family’s way out of poverty by writing his heart out. His career had started with his boss pulling him out off the print shop floor and into the writers’ room after he submitted anonymous essays to the editors that were widely popular.

George worked on his masterpiece, Progress and Poverty, for years and in 1879 he was finally able to publish his work despite rejection after rejection.

This guy was considered for his time to be as famous as Mark Twain and Thomas Edison. Progress and Poverty was at one point the highest-selling book on the market, second only to the Bible.

Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill, both President Roosevelts, Leo Tolstoy, Bertrand Russell and Aldous Huxley all hailed George’s book as a masterpiece of economic, political and philosophical thought.

Even Helen Keller read it and left a review finding “Henry George’s philosophy a rare beauty and power of inspiration, and a splendid faith in the essential nobility of human nature”.

George was not one of those Kafkaesque authors who died before he could see his work influence people. He became a household name in the late 19th and early 20th century as an international authority on tax policy in Ireland and Australia, a political candidate in New York that won more votes than pre-White House Teddy Roosevelt, and he even had a brand of cigars named after him.

George’s book inspired an international “Single-Tax” movement. George identified the cause of all economic inequality and inefficiency in the inequality and inefficiency of land ownership.

What was in this book that made it so impactful? And why has this popular historical figure and his influential book faded into almost complete obscurity?

Since land is where all wealth comes from and all trade happens on, George highlighted the fact that the biggest landlords had a uniquely powerful position over any economy and society. He was popular for taking the complex economic and political theories of fancy academic institutions and public policy offices and distilling it into an easy to understand concept for working people.

The land-value tax solution

His major policy proposal in the book was to shift the tax burden away from workers, commerce and trade and onto the unearned income of economic rents, thus fully financing the government with a progressive tax system while also creating a libertarian’s utopia of a private sector free from taxes.

Henry George’s big solution makes clear why he was so popular in his time and also why he has since been largely forgotten. Landlord monopolies have a great deal of money to influence politics, to establish universities and to staff economics departments.

I don’t suggest any kind of massive Pizza Gate-level conspiracy theory, but it is not difficult to see a simple conflict of interest causing political leaders and economics professors to be more likely to focus on issues that do not have anything to do with the land question or the private rent capture that donors, investors, and lobbyists profit from.

I remember the day I discovered that dumpster. It drove me into a whole new obsession. I took all of this new found information to my colleagues and you know what happened? I was laughed at!

“Land isn’t important anymore, that is some 1800s economics that doesn’t apply to the economy today,” my boss would say. He threatened to fire me if I turned in one more report on how landlord monopolies were stealing publicly created wealth, and letting taxes fall on workers and local businesses.

I had to get away from that soul-sucking desk job and I had to tell everyone about Henry George’s idea. I walked out of that office for the last time that day and threw my gray company clothes in the dumpster. But before I shut the lid, I noticed perfectly good and colorful economist clothes and glasses. A sign of my new-found freedom.

I donned my new (used) garb and set out on a mission to educate the world on the wealth that is being stolen from everyone — from right out under their feet. I knew I had to put my money where my mouth was, so after eating every dollar I had in my wallet for nutrition, I swore to never pay rent or sign on to a mortgage until the land and commons belonged to the people once again.

Public parks and dumpsters provide everything a man needs, and the land is held in trust by communities instead of rent-seeking banks and landlords. The park bench, the open street dumpster, the sidewalk and the public library internet are all symbols of America’s last remaining commons. They need to be used and protected.

I called myself a georgist, and aimed to carry on the land value tax reform mission despite limited resources and lacking the clout that the Single Tax movement once had.

I know there are others like me, working people who take time out of their day to study the financial and natural resource economy and uncover the source of poverty, unjust taxes, and inequality of today. This is where the greatest forgotten movement since Occupy Wall Street will make its comeback.

I also abandoned mainstream economics that day because I was sick of so-called “experts” feeling they deserve to run everything. I saw that anyone can be an economist and that we are all made homeless by the corporations that own our land. We need an army of homeless economists.

That is the big take-away from my story as well as Henry George’s story. If I can do it, (and I’m wearing a child’s clip-on tie I found in a church dumpster and a mustard stain on my $5 Goodwill pants as of the writing of this) anyone else can, too.

I maintain that most people are homeless and don’t even realize it. Since land ownership is concentrated in the hands of a well funded minority, the majority of people are forced to rent the land they live on — either directly from a landlord or through a mortgage lender.

My vision is that one day, when people educate themselves on the land question the way I did and the way Henry George did, we will have a movement of homeless economists who can work towards building a nation of Americans who are all homeless economists.

This article appeared in The American Commons.