While the majority of Americans may have a roof over their heads, they are not home. Economic forces have alienated us from the land. If the air could be privatized the way the land is, we would be taking out 30-year loans to pay for breathing privileges. They have a house, but they are homeless.

What is the difference between a house and a home? We use those terms interchangeably, but next to each other, the difference is intuitively clear.

A house is a built structure in a physical place. A home has a much deeper emotional, cultural and even spiritual meaning. Having a home means you have the right to exist and live in this world. It’s perhaps the most basic and fundamental human right.

The father of homeless economists everywhere, Henry George, wrote in A Perplexed Philosopher (1892):

“Each man has a right to use the world because he is here and wants to use the world. The equality of this right is merely a limitation arising from the presence of others with like rights. Society, in other words, does not grant, and cannot equitably withhold from any individual, the right to the use of land. That right exists before society and independently of society, belonging at birth to each individual, and ceasing only with his death.”

Most Americans are homeless and don’t even realize it.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness reports that nearly 600,000 in the U.S. are unhoused, but for even those with access to housing, about half of renters are forced to spend more than 30% of their incomes to keep themselves from joining the unhoused.

If you are a student who lives on a university campus or in an off-campus apartment, your rent might be another part of your total college debt. About 38 percent of students took out a loan in 2015 according to New America, and three-quarters of those loans included more than just tuition and fees, meaning they were most likely spent on living expenses.

Obviously, renters do not own their own homes and can therefore be considered not unhoused, but homeless. Many of America’s so-called “homeowners” are also housed but homeless, too.

The fellas over at Lending Tree noticed more than 70 percent of consumer debt is from mortgages. Mortgages are sums of money banks lend to people so that they can purchase real-estate like houses, and use the house as collateral.

It is interesting how loans specifically for acquiring land get a special name. Not to mention with the such beautiful Old French and Latin root words like “gage” meaning “pledge” and “mortus” meaning “death”.

Not many industries other than banking can sell you something called a death pledge, and have you sign it with a smile before sending you on your way with a root beer sucker.

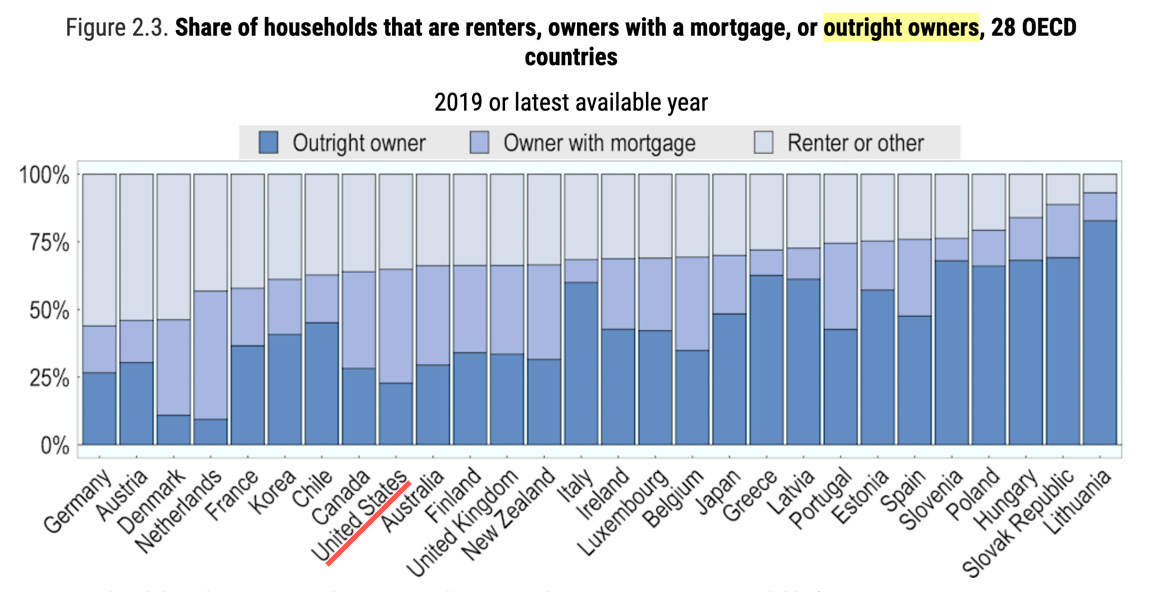

John Wake from Real Estate Decoded said that “the U.S. is a mortgage-ownership society, not a home-ownership society” when he found that the U.S. has the third lowest rate of mortgage-free homeowners in the developed world.

That is not even including other ways regular homeowners go into debt to try to scrape together enough money for a house. Some choose short-term refinancing, home equity lines of credit or to look for quarters and dimes from under the seats of people’s unlocked cars in the parking lot and leave I.O.U. notes (that last one is probably just me).

Mortgage-holders: You may not be unhoused, and you may not be a renter, but I am afraid to say that you are homeless when a bank owns your property and allows you to occupy it until you have appeased them.

The last bastion of true homeowners, the fortunate some 23 percent (mostly boomers) who were able to get to the end of their long debt slavery and pay off their home loans, or just buy their houses outright, will likely eventually be bought out of their properties by banks and corporate landlords like BlackRock, JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs in the foreseeable future.

This same situation looked at from another angle is why so many people are priced out of the housing market in the first place.

Regular people looking for places to live cannot compete with land speculators, monopolies and financial institutions.

We have an economic system that incentivizes land-hoarding and rent-seeking by those with the fat stacks to get into that business, but discourages building and constricts the housing supply. It becomes more profitable to own land and extract rent than it is to develop it into something for the betterment of society.

It does this through the broken property tax system. Plots of land with decaying or nonexistent buildings are taxed less than plots of land where people went through the trouble to build nicer and more comfortable homes.

The value of land itself comes from nature and the productivity of the local community. On the other hand, the value of buildings and houses comes from the labor and material risk of private individuals.

However, with the upside-down property tax system we have, private landowners take the publicly-created value in land, while the government taxes the privately-created value of buildings.

We need not tolerate this system. It doesn’t need to be molotov cocktailed, either.

If the value of land were returned to the general community, and the value of buildings and paychecks were returned to the risk-taking and hardworking home builders, then we will be on our way to ample homes and jobs.

This is a simple explanation of Henry George’s remedy, the land value tax shift, also known as the “Single Tax” because of its ability to replace nearly all other burdensome taxes on wages and business.

The idea is very flexible. You could have a large-scale public land leasing system like Singapore’s where the only landlord is the government, or a natural resource wealth fund like Norway’s where they use the wealth of their oil to pay for certain welfare services for their citizens.

You could have a modest split-rate tax like many Pennsylvania communities have (like a diet Coke version of the Single Tax Coca Cola that returns a little bit of the land value to the public but still taxes buildings as traditional property taxes do).

Or you and your friends could get together and create a community land trust (CLT) which implements the land value reform idea on an even smaller scale with a few local pieces of land.

What all these examples have in common is the idea of publicly-created wealth paying for public projects and privately-created wealth being left alone for the individuals who bother to get up in the morning and go to work to create it.

In one way or another, every instance of a community having the nerve to stand up and start returning the values of land and natural resources back to the public, while giving full wages and profits back to working families and entrepreneurs, has shown strikingly consistent results.

Those being: housing becomes affordable, jobs become plentiful, local businesses grow and the people in those communities finally feel like they are home.

There is still a small band of remaining Georgists fighting for such reforms. that have been in the land value tax shift game since before I was in reused / disposable dumpster diapers.

They are like Robinhood and the Merry Men except the historically accurate version; not stealing from the rich but instead reclaiming the forest from feudal landlords who began enclosing the once free-to-use ancient English Commons.

But that is a story for another time.

In the meantime, consider playing a part by reaching out to your city, county and state lawmakers to advocate for a land value tax shift or split-rate property tax in your area.

Organizations like Just Economics LLC, Urbantoolsconsult.org, the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, The Schalkenbach Foundation and Common Ground USA are all great resources to learn more about and get involved with the American land and tax reform movement.

This article appeared in The Indiana Commons.

If you live in an HOA, you too are temporarily housed.